What is polycythaemia (rubra) vera (PV)?

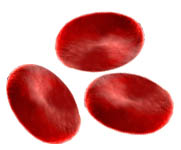

Polycythaemia (rubra) vera, (PV) tends to produce an over abundance of erythrocytes, (red blood cells), than is considered normal. Often PV can also affect the production of other blood cells, for example your body may also produce too many platelets, (Thrombocytes), and white blood cells, (Leukocytes).

Research has shown that nearly 97% of people with PV have a mutation (or change) in a protein called JAK2, a protein that is part of the mechanism which regulates blood cell production in our bodies. The cause of this mutation presently remains as unknown but may result from viral infections or radiation damage, and just another reason why more research needs to be done to establish the causes of PV.

PV is considered to be a rather rare MPN condition, although in Australia, we are still collecting data and it might be sometime before enough quantitative studies have been completed before we know the real incidence of all MPNs here in Australia.

In the UK & European experience, MPN Voice suggests that the number of people is 2 people per 100,000, and that more men than women suffer from PV. PV primarly affects the elderly and is rarely seen in the young.

According to one Australian study, there might be a diminishing incidence of PV in Australia, (as in Norway), and an increase in ET, (Baader et al 2018)

Diagnostic tests

Several tests are used to confirm the diagnosis of PV and to help your haematologist to understand your condition. You may need to undergo some of the following tests:- Full blood count (blood test): Your haematologist may repeat this test for verification if the test was previously done by your GP.

- JAK2 test: Your haematologist can test your blood to see if you have a change (or mutation) called JAK2 V617F. Approximately 95% who have PV have this mutation. A further 2% of patients have a mutation in another part of the JAK2 gene called exon 12.

- Abdominal ultrasound: If you have PV, your spleen may be enlarged. This is because in PV your spleen may begin to produce blood cells, and these collect inside the spleen. The ultrasound is a painless test. Spleen examination can also be done by feeling your tummy.

- Bone marrow biopsy (BMB): A bone marrow biopsy is a test of your bone marrow that is done in the hospital. You will not need to stay overnight in the hospital, and you will generally just need local anaesthesia. Your haematologist will give you some medication to prevent pain, and then he or she will extract some bone marrow from your hip bone using a needle. The bone marrow tissue can then be examined in a laboratory so that your haematologist see how the cells in your bone marrow are functioning.

"Additional tests might also be required but no doubt your medical team’s advice is the best way to move forward…"

Symptoms

In the early stages, PV patients may not exhibit any signs of the disorder but as the condition progresses a patient may exhibit some of the following symptoms:

- Redness of skin (plethora)

- Blurred vision and headaches

- Bleeding and/or clotting

- Skin itchiness (pruritus)

- Joint pain or gout

- Dizzy spells

- Fatigue

- Unexplained weight loss

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Fullness/bloating in the left upper abdomen due to enlarged spleen

Complications

People with PV are at a high risk of blood clots (thrombosis) and bleeding (haemorrhagic) events. The chance of both bleeding and clotting complications of PV can be reduced with medication to reduce blood stickiness and also lower the red blood cell and platelet counts. Clotting episodes are more common than bleeding episodes and they have a significant impact on survival. Examples of the different types of blood clots include:

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

- Pulmonary embolism (lung clot)

- Myocardial infarction (heart attack)

- Cerebrovascular accident (stroke)

- Minor thrombotic events (minor clots)

- Transient ischaemic attack (TIA – minor stroke)

- Superficial thrombophlebitis (varicose veins)

- Erythromelalgia (painful and swollen finger/toe)

Treatment

The aim of PV treatment is to control complications and reduce the number of red cells and platelets in the blood. Venesection a process or removing blood from the body), and drug therapy can be used to reduce the number of red cells and to slow their production. Your haematologist will determine your treatment for you individually based on your age, how well you tolerate venesection, your red blood cell count, and your history of clotting or bleeding complications.

Greater awareness and research is urgently needed to stop the rising number of Australians dying from blood cancer says Leukaemia Foundation (SBS 2017)

Prognosis

If you have PV, your prognosis depends on many factors including your age, other illnesses you have, and PV complications you may develop with PV. Blood clots (thrombosis) are common and are frequently serious; the risk of these events increases with age and previous episodes. The goal of PV treatment is to reduce the risk of complications and prolong your life.

Patients who do not suffer from other diseases (especially MF or leukaemia) have a normal to slightly reduced life expectancy.

About 15% of people with PV develop a complication of the disease known as myelofibrosis (MF). Please visit our Myelofibrosis page for more information about this disorder.

Some patients with PV transform to Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML). The onset of AML is rare but can have a poor outlook, as this form of leukaemia is often resistant to treatment. If this is a concern for you, please discuss this with your haematologist.

Common side effects

You may feel tired after giving blood, and you may have some local soreness or bruising, but serious side effects are very uncommon. Some people faint after giving blood, if you feel dizzy or unwell in the 24 hours afterwards tell your team and they may give you some fluid (salt water) to replace the volume lost in the blood. This is more likely to happen if you are taking tablets for blood pressure and if you have not eaten before attending the hospital.

Venesection (phlebotomy)

Taking blood – called venesection or phlebotomy in medical language – reduces red blood cell counts in people with polycythaemia vera (PV). It has very few risks. If you have polycythaemia vera (PV) you have too many red blood cells. One way to reduce your red cell count that does not require any medication at all is to use a procedure called venesection or phlebotomy.

It’s a simple procedure done just like having a blood draw or making a blood donation – a doctor or nurse inserts a needle into your vein and collects some blood. Patients with PV usually have about anywhere from 350 ml to 500 ml of blood removed during venesection. The amount depends on your height and weight as well as your haematocrit, (blood thickness or packed cell volume level) and your general state of health.

How it works

Phlebotomy (or venesection) is a standard treatment for PV and helps bring your red cell count closer to normal. Your haematologist will ask you to come to hospital to have some blood removed. It works in the short-term since you make up the liquid part of your blood (plasma) quicker than red cells and in the long-term iron stores are reduced slowing down the production of red cells. For this reason it is very important not to take iron if you are a patient with PV.

You may need regular venesections every few weeks or months until you reach an acceptable blood thickness level. Your target blood thickness (haematocrit) depends on your risk factors, how well you tolerate the procedure and whether you’ve had any previous complications such as a blood clot.

Top tips

These are top tips for phlebotomy shared by people with PV. Share your top tips with us on the ‘FORUM’ or by emailing us at info@mpn-mate.com.

- Fainting: You can prevent fainting by eating something before your venesection. Don’t skip breakfast!

- Replenish: Drink plenty of water before and after venesection and be careful of dehydrating drinks.

- Take it easy: Plan a restful time after your venesection. You may feel a bit tired so you don’’t want to schedule too much.

- Let others know: Tell family members and others you trust that you are having a venesection so you may need a little extra help, for instance if you are caring for young children.

- Arrange transport: You may be too tired to drive or travel by public transport right after a venesection, in particular if you are feeling fatigued for other reasons, for instance as a side effect of your MPN.

- For women: It is best (although not essential) to schedule venesections for a time of the month when you are not menstruating. This will prevent you from feeling excessively tired after venesection.